Drilling near the Apalachicola River: Is it legal? A judge will decide after a hearing this week.

Opponents to exploratory oil drilling near the Apalachicola River are calling on officials to scrap the proposal, as an administrative court hearing gets underway this week.

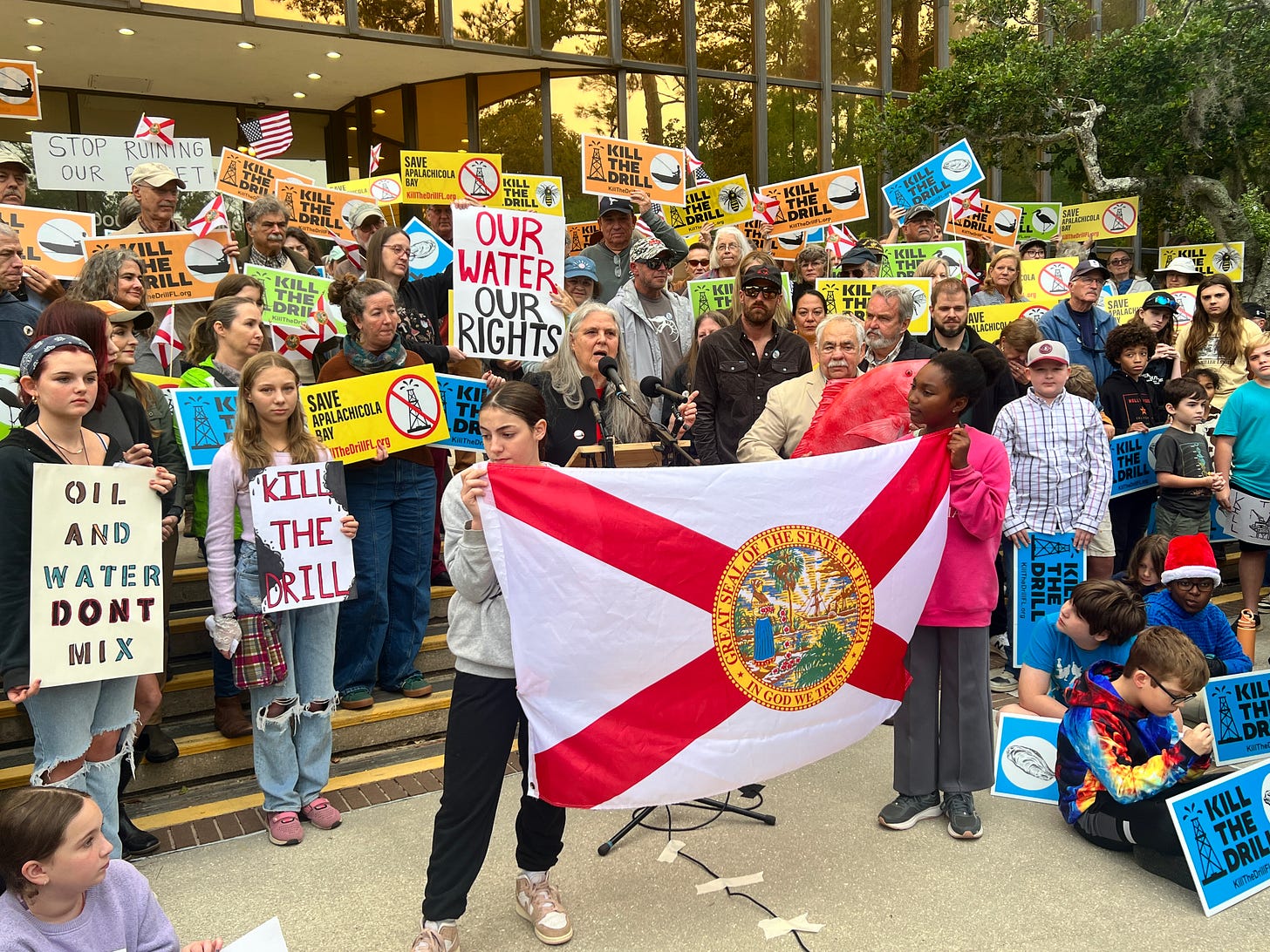

Hundreds of local residents who oppose drilling near the Apalachicola River gathered outside state environmental offices yesterday to send the following message: “Kill the Drill.”

“If there is one clear, land-use principle, it’s that you don't put heavy industrial uses adjacent to the most pristine environment that we have — one of the most pristine environments we have left in the entire world,” said Susan Anderson, executive director of the Apalachicola Riverkeeper, a nonprofit organization that works to protect the river and bay.

Anderson was among about 350 people who crowded together in front of the Florida Department of Environmental Protection headquarters on Monday afternoon after a week-long court hearing over the proposal got underway on the other side of town.

“Write letters to the governor,” Anderson reminded the crowd, which included coastal residents, small business owners, environmental advocates and dozens of elementary and middle school students from a nearby private school. “Write letters to your representatives.”

In April, the department signaled its intent to allow Clearwater Land & Minerals FLA LLC to look for oil in a wooded area in Calhoun County, about a mile from the riverbank and in the river’s floodplain, by issuing a draft permit.

There are two ponds and two streams located within a one-mile radius of the proposed oil drilling site, and one of those ponds connects to the Apalachicola River, according to the company.

Local and state elected officials and residents along the “Forgotten Coast” — which stretches across Gulf, Franklin and Wakulla Counties — have voiced concerns about possible harms to local economies and the river, bay and other connected waterways.

A judge will weigh in on the legality of the drilling permit after a week-long court hearing ends

In a petition filed in June, the Riverkeeper asked an administrative law judge to recommend the department to deny Clearwater’s permit application on the basis that it would violate state laws.

“There’s a hundred percent evidence of no oil, and no clear evidence of finding oil,” Anderson said.

Attorneys for the Riverkeeper, Clearwater and the state are presenting evidence in front of Administrative Law Judge Lawrence Stevenson throughout the week at the Division of Administrative Hearings in Tallahassee.

Judge Stevenson will issue a recommendation to the department on the legality of the permit, but the department has the final say on whether or not to issue one.

Either side has the option to challenge the department’s decision in the Florida First District Court of Appeal.

Attorneys for Clearwater argue that they have demonstrated that there’s a likelihood of finding oil “on a commercially profitable basis” and that the plan complies with all state laws and administrative rules governing drilling.

The department’s attorneys have also said that the drilling permit application meets all requirements under the law.

David Guest, an environmental attorney who wrote arguments against allowing drilling in that area on behalf of the Riverkeeper in 2018, said he thinks the Riverkeeper filed a “well-thought-out” petition and he agrees that allowing the company to look for oil would violate permitting standards.

The legal standard that’s used to determine whether or not drilling is permissible in Florida is based on a balance of considerations outlined in state statute, which include the “proven or indicated likelihood” of finding oil on a “commercially profitable basis”; the nature of the lands involved; and whether there’s a risk of an adverse event to health and public safety, Guest explained.

Over the decades, 70 exploratory oil wells have been drilled in Calhoun County and five surrounding counties, but all of them have come up dry, state permitting data shows.

“Not a mouthful, not a teaspoonful [of oil] has been recovered — and it's been drilled like a pincushion,” Guest said. “If they were honestly applying the legal standard of the likelihood of commercially-recoverable oil, they wouldn't do it.”

Additionally, he said he thinks the drilling plan would violate other criteria within the law

“You're really in a pretty sensitive area that's really, pretty inappropriate for drilling,” Guest said. “It's surrounded by water at high water, the entire drilling pad is surrounded by that.”

In 2018, the department granted a permit to Cholla Petroleum, allowing them to look for oil where Clearwater wants to explore. The draft permit was never challenged in court before the final authorization was issued, but drilling never happened and the permit expired. The drilling pad and other infrastructure, however, remained at the site.

“Just because they issued a permit previously for another applicant that was never challenged doesn’t necessarily mean another applicant gets to come along and automatically get a permit,” explained Terrell Arline, a land use attorney with experience in environmental law.

The drilling proposal has received widespread opposition from local residents

The press conference, which was organized by a coalition of 67 small businesses and environmental groups — including the Riverkeeper and the Downriver Project, a nonprofit coalition that advocates for protecting waters in the region — is the second gathering this year where the “Kill the Drill” mantra was prominent.

In June, state Sen. Corey Simon (R-Tallahassee) voiced his opposition to the drilling proposal at a fundraising event in Apalachicola hosted by the Franklin County Republican Executive Committee.

If oil is discovered, drilling opponents say they fear the risk of a leak or spill that would devastate the river and bay, and the local economies that rely on its health, for years to come. Even if there’s no blowout, they say the perception of oil drilling near the water could hurt tourism and small businesses.

Crawfordville resident David Damon, who owns a hurricane shutter business, recalled the hit to the tourism industry that the area took after the 2010 BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico.

“You don't even have to have tarballs watching up on the beach, just a threat that that oil is there,” said Damon, while speaking during the press conference. “And people cancel, people go home, they don't want to come to a place like that.”

Hundreds of Gulf County residents, the board of county commissioners and the leaders of every town in the county have sent letters to the department voicing opposition to the drilling permit, said Deb Mays, who spoke on behalf of the Gulf County Citizens Coalition.

“I'm here today to plead with the powers that be, whoever they may be, that makes this decision to recognize not only one county, but two counties, have a stake in this and to please stop this drilling, not just this time but forever,” Mays said.

Local elected officials in Franklin County have also sent letters to the state in opposition to the drilling plan.

Republican state Rep. Jason Shoaf has also expressed his concern about harms that nearby drilling could bring to the river and bay.

Despite the widespread opposition to the plan, the governor’s office hasn’t responded to a request for comment on the issue.

Susan Anderson, with the Riverkeeper, says that she hopes the governor will use his political power to pressure DEP to deny the permit. “The governor is the governor of the people of the state of Florida,” she said. “Clearwater is a Louisiana Company that’s coming in.”